No one wants their gadget to have crappy battery life, but it’s particularly annoying with wearables. If that new fitness tracker needs to be recharged too often, it’s going to collect dust in a drawer somewhere. Well good news, everyone. Scientists have figured out how to build a wearable thermoelectric generator that’s super stretchy, self-healing, recyclable, and may one day power wearable devices and the Internet of Things.

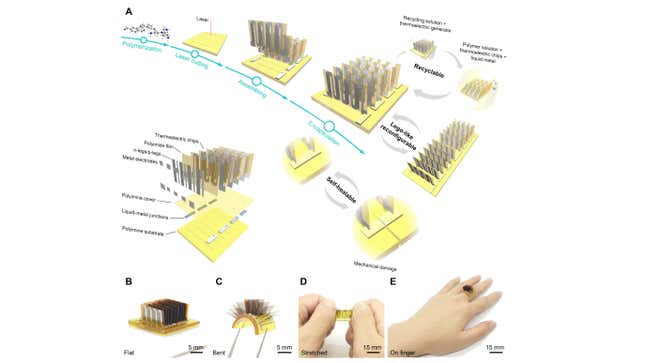

In a paper published in Science Advances, scientists managed to combine modular thermoelectric chips with a “dynamic covalent polyimine” and liquid-metal wiring into a flexible mechanical architecture. The end result allowed them to put the chips into a super stretchy material that not only self-heals when damaged but can be rearranged like Legos into multiple configurations. And as a bonus, the design also led to a “record-high open-circuit voltage” of 1V per centimeter squared. This is all a fancy way to say “Hey guys, we figured out a way to get a record amount of power by harvesting heat that doesn’t require a rigid, inflexible composition and is actually pretty durable.”

This is neat from a gadget perspective because thermoelectric generators open up the possibility of generating electricity by harvesting energy from heat. It’s sort of similar to The Matrix but much, much, much less dystopian. Theoretically, you could get around the whole battery problem with smartwatches and other wearables by using thermoelectric tech to turn body heat into electricity that can then power your device and eliminate the need for charging. (Actually, it’s less theoretical as there is a smartwatch that does just that, albeit not very well.)

The issue is that wearable devices—and the sensors inside them—need more power to run continuously than thermoelectric generators have been able to create thus far. Plus, people are pretty hard on their smartwatches and wearables. They have to withstand daily tasks that might not be electronics friendly, like dishwashing. They have to be flexible and durable enough to handle lots of bouncing around during exercise, as well as accommodate different body shapes. Thermoelectric generator chips are notoriously rigid and brittle, so the fact that scientists have figured out how to house them in a stretchable material without breaking is huge. Also encouraging is that the scientists say that from a typical sports band of roughly 2.3 inches (6 centimeters) by 9.8 inches (25 centimeters), their design is capable of generating 5 volts of power just through walking. That, they say, is enough to “directly drive most low-power sensor nodes with radio frequency communication.” It’s not everything, but it’s definitely a workable start.

But one of the really cool things is that this particular device is self-healing. Because it uses liquid-metal wiring, should it break, the two parts can be brought back into contact and re-establish electrical conductivity in about 90 minutes. This also means you can cut and reattach the device into different configurations, and it would still work. And since the device is also built using polyimines, it can easily be broken down into separate components by soaking it in a special solution. That solution can then be used to make a new polyimine film, which can, in turn, be used to generate a new thermoelectric generator device from all of the old components.

This is exciting from an e-waste perspective. Not only are batteries crap for the environment, but major wearables companies are also just as guilty as phone makers when it comes to “forcing” customers to unnecessarily upgrade perfectly usable devices every one to two years. While some gadget makers have introduced recycling programs for phones and speakers, they’re not that common for fitness trackers and smartwatches. In addition to potentially reducing reliance on batteries in the first place, the recyclable aspect of this design might incentivize manufacturers in the future to collect wearables using this tech and reuse their components.

This is all promising, but it doesn’t mean that your next Apple Watch will harvest your body heat. This is just initial research and there’s no guarantee that big wearables makers will adopt it in consumer electronics. Implementing it would have to be cost-effective, scalable, as well as easy for consumers. That said, it’s definitely an interesting solution worthy of further investigation and research.