Two U.S. children in recent weeks appear to have been killed by a dangerous amoeba found in freshwater lakes and ponds. On Tuesday afternoon, North Carolina health officials reported the death of a young boy due to a brain infection from Naegleria fowleri, a rare but often deadly disease spread by contaminated water shooting up through the nose into the brain. Also this month, the family of a young boy in Northern California said he had died from the same amoeba after swimming in a lake.

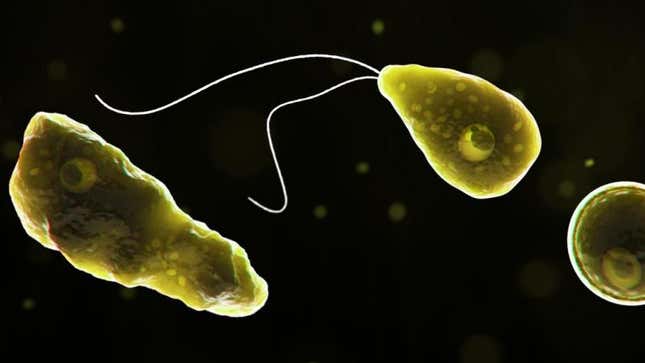

N. fowleri is a free-living amoeba (“amoeba” is a catch-all term for many microbes, defined by their ability to shapeshift into different forms and their finger-like projections used for movement, called pseudopods). It most commonly hangs around in warm bodies of freshwater or the surrounding soil. Ordinarily, the amoeba only feeds off bacteria, and simply swallowing water containing it doesn’t hurt us. But if N. fowleri finds its way into the human brain, it develops a hunger for certain types of cells and triggers an brain-destroying infection known as naegleriasis, or primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM).

Usually, the infection happens when someone accidentally gets water up their nose while swimming. But it has also rarely happened when people unknowingly use contaminated water to irrigate their sinuses in order to clean out mucus and debris. Neti pots, a popular nasal irrigation product, have periodically been linked to PAM cases.

Symptoms of PAM can take a day to over a week to appear following exposure. They include headache, nausea, confusion, and other neurological problems. Unfortunately, the infection is nearly always fatal, even when treated with heavy doses of antimicrobials, and victims tend to die within a week of symptoms starting. Thankfully, the disease is rare: Only about 400 cases have ever been documented since its discovery in the 1960s, with most in the U.S—rare, but not non-existent, sadly.

On Tuesday, North Carolina officials announced that an unidentified young boy in the state had died last Friday “after developing an illness caused by an amoeba that is naturally present in freshwater.” The boy had recently gone swimming in a private pond. Testing from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed that the culprit was N. fowleri.

“Our heart-felt condolences and sympathies are with the family and friends of this child,” Zack Moore, state epidemiologist, said in a statement released by the health department.

On Monday, the Los Angeles Times reported on the death of a 7-year-old boy in the state, also seemingly due to N. fowleri. The boy’s aunt had started a GoFundMe on the family’s behalf on August 4, where she stated that he had gone to the emergency room on July 30 and had been hospitalized with severe brain swelling and placed on life support. He reportedly died eight days later, diagnosed with N. fowleri infection. The family has asked for people to donate to the Kyle Cares Amoeba Awareness Foundation, a charity started a decade ago by the family of another young victim of the amoeba.

Rare as these infections are, they’re also preventable—a point that North Carolina officials were quick to emphasize. “[T]his is an important reminder that this amoeba is present in North Carolina and that there are actions people can take to reduce their risk of infection when swimming in the summer,” Moore said.

These steps include limiting the amount of water that goes up the nose while swimming in warm freshwater sources—pinch your nose shut with your fingers, example, when jumping in—and not using standard tap water for nasal irrigation or other practices where water could get into the nose, like certain religious rituals. Any water that does get used for these activities should be sterilized first, which can include boiling.