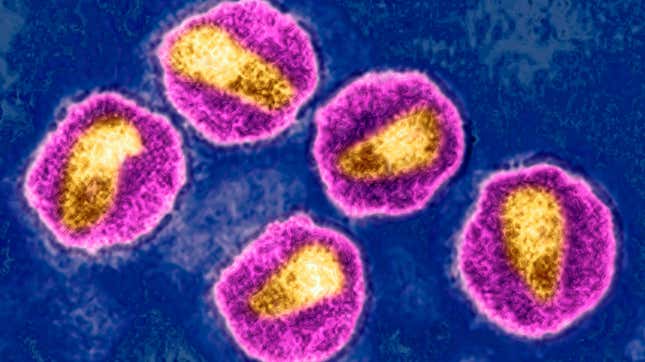

Researchers in a new paper this week say that a highly virulent variant of HIV has been silently circulating in the Netherlands, likely for decades. Thankfully, the variant still responds to conventional treatments and its spread appears to have declined in recent years. But the discovery may offer a timely lesson about the nature of germs like HIV and how they can evolve over time to become more dangerous.

The researchers, based in the UK and elsewhere, had been working on the BEEHIVE project, a study meant to figure out why some strains of HIV can cause more harm to a person’s immune system than others when left untreated—the end result of which leads to AIDS. To do this, they studied samples from people infected with HIV throughout Europe and Uganda, including those collected by earlier studies, hoping to find common mutations that could make the virus more damaging.

During this search, they found a group of 17 people, mostly from the Netherlands, who all carried the same variant of HIV-1, the most common type of HIV. This version of the virus—eventually christened as the “VB variant”—appeared to be exceptionally high in virulence. In practice, this meant that people with VB had far higher viral loads than usual and their levels of CD4 cells, the immune cells that HIV primarily infects and kills, dropped off very rapidly as well.

To confirm their suspicions, the team dug into another database of HIV patients living in the Netherlands. Sure enough, they found the variant in more people there as well. All told, they’ve identified VB in 109 people so far. And these individuals seemed to be no different from other residents in the country living with HIV in their age, sex, or other characteristics, further indicating that the virus itself is responsible for the increased virulence seen in their cases. The team’s findings were published Thursday in Science.

“Before this study, the genetics of the HIV virus were known to be relevant for virulence, implying that the evolution of a new variant could change its impact on health. Discovery of the VB variant demonstrated this, providing a rare example of the risk posed by viral virulence evolution,” said lead author Chris Wymant, a researcher at the University of Oxford’s Big Data Institute and Nuffield Department of Medicine, in a statement from the university.

VB certainly does pose an added danger for those unlucky enough to contract it. Because CD4 cells decline so rapidly with this infection, Wyant and his team estimate that it would take as little as nine months for someone to develop AIDS (typically, it can take years). People’s higher viral loads would also likely make them more infectious to others. But fortunately, VB doesn’t seem to behave any differently from other HIV strains once people get on antiretroviral therapy, meaning the treatments can still suppress the infection and make people less or even completely unable to pass the virus to others.

By studying its genetics, the team also found evidence that VB may have first emerged in the 1990s. And though it might have spread more rapidly in the early 2000s, its spread has likely slowed in the last decade. In other words, while VB is an important discovery, it doesn’t appear to be a major public health threat at this time.

VB might also offer some broader lessons about viral evolution, which are all the more relevant in our pandemic times. It’s often claimed by those seeking to downplay the pandemic, for instance, that harmful viruses inherently and inevitably become milder over time, since it would allow them to infect more people who don’t die from it. In truth, the process of viral evolution is more complicated than that.

The transmission potential of a germ can be negatively affected by its fatality, such as with Ebola. But viruses like SARS-CoV-2 are so transmissible early into an infection that it may not be pressured to change much at all, and even a deadlier version of it can still easily thrive, since it can take weeks for people to die as a result of infection. Indeed, we probably saw this happen with the emergence of the Delta variant of covid-19, which appears to have caused more severe illness than past strains. With HIV, its ability to cause illness and eventually kill people seems to be tied to the same attributes that allow it to be transmitted more easily. So a variant that’s deadlier may still gain a foothold if it’s also more transmissible, at least up to a certain point, as VB and possibly other strains seem to have done. Other factors outside of the germ itself, like our preexisting immunity to it, also play a role in determining how mild it can be as an illness.

That’s not to say that widespread strains of a virus can’t become milder either—something we’ve perhaps now seen with the Omicron variant of covid-19. It just means that predicting the trajectory of virulence for any germ isn’t so easy, including for the coronavirus. In an op-ed discussing the new findings, Joel Wertheim, an evolutionary biologist from the University of California, San Diego, makes a similar point.

“Although it is certainly possible that SARS-CoV-2 will evolve toward a more benign infection, like other ‘common cold’ coronaviruses, this outcome is far from preordained,” Wertheim warns.

As for VB, the researchers say its emergence isn’t a sign that our current strategy against HIV isn’t working. Some researchers have argued that treating certain infections can actually promote the evolution of highly virulent variants, possibly including HIV. But the researchers argue back that VB seems to have arisen in spite of these treatments, not because of it. And since even people with VB given early treatment are less infectious, it only shows that effectively containing the virus is still the best way to keep variants like VB from spreading further.

“Our discovery of a highly virulent and transmissible viral variant therefore emphasizes the importance of access to frequent testing for at-risk individuals,” they wrote, “and of adherence to recommendations for immediate treatment initiation for every person living with HIV.”