Using high-resolution, 3D X-ray scans, a team of researchers has digitally unwrapped and analyzed three mummified animals from ancient Egypt.

A kitten with a broken neck, a bird of prey, and a dehydrated snake with a fractured spine are now teaching us a bit more about ancient Egyptian customs. These fascinating observations were made possible through the novel use of X-ray microcomputed tomography (microCT). The resulting study, published today in Scientific Reports, is shedding new light on the ancient practice of mummification, including insights into the lives and deaths of these animals and the highly ritualistic methods employed by ancient Egyptians as they prepared their spiritual offerings over 2,000 years ago.

Ancient Egyptians were often buried with mummified animals, but a more common cultural practice involved the use of mummified animals as votive offerings, as the researchers explained in the study:

Gods could also be symbolised as animals, such as the goddess Bastet, who could be depicted as a cat or other feline, or a human with feline head; and the god Horus who was often depicted as a hawk or falcon. Mummified animals were purchased by visitors to temples, who, it has been suggested, would offer them to the gods, in a similar way that candles may be offered in churches today. Egyptologists have also suggested that the mummified votive animals were meant to act as messengers between people on earth and the gods.

Animals were either bred or captured for this purpose and then killed and preserved by temple priests. An estimated 70 million animals were mummified in ancient Egypt over a period of 1,200 years, in a practice that reached industrial levels of production.

For the new study, Richard Johnston from the Materials Research Centre at Swansea University sought to evaluate the potential for microCT scanning to assist archaeologists in their work. Resolutions produced by this technique are 100 times greater than regular medical CT scanners, and it’s ideal for studying small samples. And unlike standard 2D X-rays, this technique offers a 3D perspective.

The system works by compiling a tomogram, or a 3D volume, from multiple radiographs. The resulting 3D shape can then be rendered digitally into virtual reality or 3D printed, providing unique perspectives for analysis. MicroCT scanning is typically used in materials science to view structures in microscopic detail, but Johnston thought it could have value in archaeology as well.

The new paper is thus a kind of proof-of-concept study. Johnston, along with study co-author Carolyn Graves-Brown, the curator of the Egypt Centre at Swansea University, wandered through the museum’s storage area in search of suitable test subjects. Of the many artifacts available, however, Johnston found the animal mummies to be the most “enigmatic.”

“I selected a few samples with varied shapes that would demonstrate the technology, without knowing what we would find at that stage,” wrote Johnston in an email. “Hence selecting a cat, bird, and snake mummy. There are many examples of these mummified animals in museums, and they have been studied through history. We aimed to test the limits of what this technology could reveal that wasn’t possible before.”

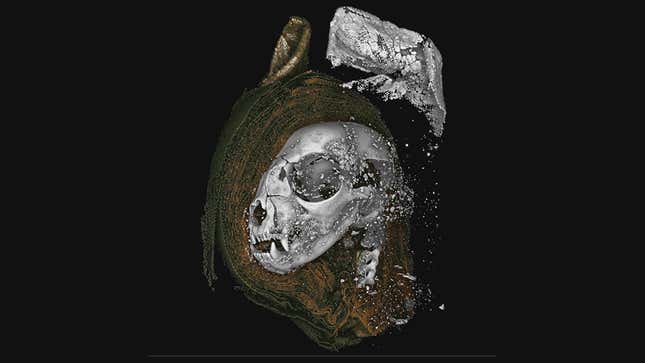

The resulting hi-res scans proved to be far superior to the traditional method of destructive unwrapping; in addition to providing a high-res view, micro X-ray scans are non-invasive, and mummified contents can be studied in their original position. What’s more, the resulting data exists digitally, allowing scientists to revisit the data repeatedly, even years later, which was the case with this project.

“One scan is around 5GB of data, yet for years it can reveal something new with fresh eyes or using new software,” Johnston said. “In recent years we’ve incorporated virtual reality into our lab using SyGlass software, so instead of analyzing 3D data on a 2D screen, we’re able to immerse ourselves within the data, which provides a unique perspective. I can scale the animal mummy to the size of a building, and float around inside, looking for fractures, inclusions, or anything interesting. This helped with measurements in 3D space to support confirmation of the age of the cat too.”

The researchers also created 3D-printed models, in which the specimens were scaled up to 10 times normal in the case of the snake and 2.5 times for the cat skull.

Analysis of the kitten showed it was a domesticated cat that died when it was less than five months old. Unerupted teeth within its mandible were made visible through the digital dissection of the virtual mummy, as the researchers could virtually “slice” through the kitten’s jaw.

“We’d missed this while analyzing the 3D data on a 2D screen, and also missed it within the 3D print too,” said Johnston.

Interestingly, the kitten’s neck vertebrae were broken. This happened either shortly before the kitten died or just prior to the mummification, and it was done to keep the head in an upright position during preservation. Study co-author Richard Thomas from the School of Archaeology and Ancient History at the University of Leicester was “able to handle an enlarged replica of the cat skull to examine the fractures in detail,” explained Johnston.

The snake was a juvenile Egyptian cobra. It developed a form of gout, likely because it was deprived of water during its life. Its calcified kidneys pointed to a state of dehydration, which likely caused it to live in severe discomfort. Spinal fractures seen on the mummified snake suggest it was killed by a whipping action—a technique commonly used to kill snakes.

A chunk of hardened resin was found inside the opening of its throat, pointing to the complex and highly ritualized nature of the mummification process. Johnston said this has parallels to the Opening of the Mouth procedure seen in human mummies and the Apis Bull.

As for the bird, it’s probably a small falcon known as a Eurasian kestrel. The microCT scan let the researchers make precise measurements of its bones, allowing for the species identification. Unlike the other two animals studied, its vertebrae were not broken.

With this experiment complete, archaeologists should now be motivated to perform microCT scans on other mummies and possibly other specimens in which details are hidden and when destructive analysis is not ideal. And as this new study shows, archaeology, which seeks to understand the past, is continually driven forward by modern innovations.