The Enormous Black Hole At The Heart Of Our Galaxy Is Flickering - Why It Matters

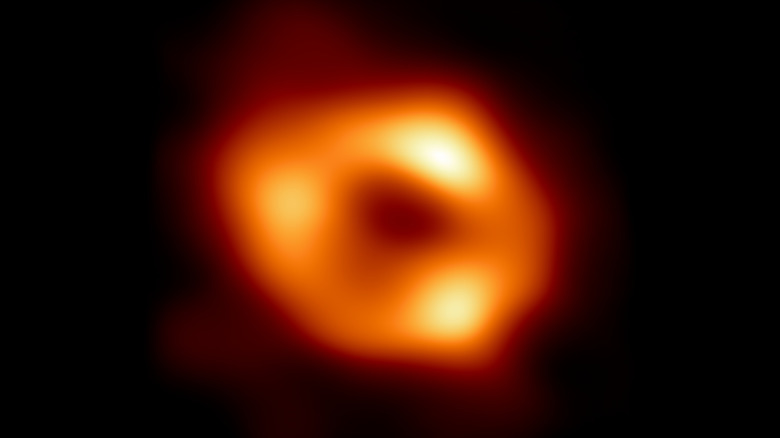

At the heart of our galaxy lies a monstrous black hole named Sagittarius A*. Almost all galaxies have such supermassive black holes at their centers, and our particular black hole had its moment of fame in May 2022 when the Event Horizon Telescope project managed to take an image of it as part of an international cooperation. This image doesn't actually show the black hole itself, which is invisible as it absorbs light. Instead, the image shows the gas around the black hole, which knocks together around the black hole's event horizon and gets hot, therefore giving off energy that can be seen by telescopes.

The glow of the gas around this black hole isn't steady, however. In fact, it flickers, and scientists are investigating this flicker to learn more about the black hole's structure. As detailed in a paper published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, researchers used this flicker to build up the most accurate model of Sagittarius A* so far (via Institute of Advanced Studies). They were able to learn about how gas moves around and into the black hole, finding that rather than eating away at nearby gas swirling around the black hole, much of the material being ingested is traveling from a significant distance away. "Black holes are the gatekeepers of their own secrets," said lead researcher Lena Murchikova. "In order to better understand these mysterious objects, we are dependent on direct observation and high-resolution modeling."

Working with the flicker

The recent paper combines the expertise of three experts who have worked on research into different aspects of Sagittarius A*. By combining large-scale observations of how nearby stars are affected by the gravity of the black hole with more detailed models of what happens to the gas close to the , they could see that the traditional understanding of black holes wasn't correct. "For a long time, we thought that we could largely disregard where the gas around the black hole came from," Murchikova said. "Typical models imagine an artificial ring of gas, roughly donut-shaped, at some large distance from the black hole. We found that such models produce patterns of flickering inconsistent with observations."

In order to explain the flickering they did see, the experts had to allow for the gas that falls into the black hole to have come from nearby stars and not just from the gas orbiting close to it. The stars near the center of the galaxy give off this gas, which is then drawn toward the black hole and eventually past the event horizon. "When we study flickering, we can see changes in the amount of light emitted by the black hole second by second, making thousands of measurements over the course of a single night," co-author Chris White said. "However, this does not tell us how the gas is arranged in space as a large-scale image would. By combining these two types of observations, it is possible to mitigate the limitations of each, thereby obtaining the most authentic picture."