An abundance of reporting has confirmed that you’re not paranoid, Minority Report was nonfiction, and face paint isn’t just an art project. We hear about how law enforcement can match our faces with photos scraped from our social media profiles and monitor us through neighbors’ doorbells. The near-weekly updates send a shiver down our spine, and we file them away along with too many instances to rattle off in a blog post. Usually, it’s up to privacy advocates to track this constant surveillance take the violations to court. But now, the Electronic Frontier Foundation has produced an easily filtered national map of implemented surveillance tools—although, the EFF disclaims in the description, the map is only the “tip of the iceberg.”

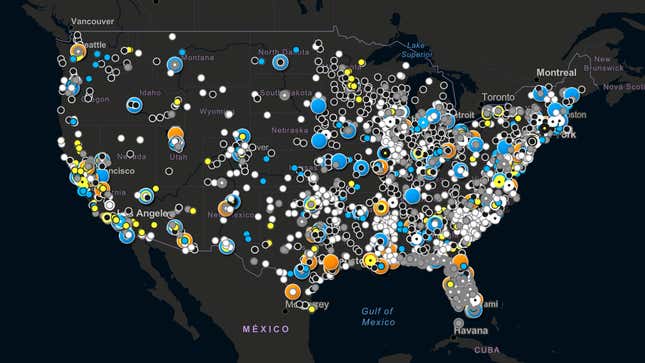

The map of 5,300 data points shows 12 types of surveillance deployed by law enforcement, including license plate readers, facial recognition, cell-site simulators, drones, and Amazon’s Ring video-sharing partnerships with local law enforcement. The EFF enlisted hundreds of journalism students and researchers whose expansive search encompasses journalists’ and nonprofits’ public datasets, government documents, vendor publications, news articles, and minutes from meetings. On the map, the U.S. looks like the site of a horrible infestation.

The EFF notes that you should take the map with a grain of salt. “With thousands of data points to go through,” reads the methodology page, “it is impossible to exhaustively fact-check each one, despite the multiple reviews by students and staff.” It says that facial recognition in particular can be hard to track, as local governments often start and stop programs involving it abruptly. It also notes that research is limited to information made available by government agencies and reporting, which can be flawed. The map is also not a complete picture of every location where one might possibly be surveilled at all times; instead, it shows jurisdictions where these technologies are in use.

We can reasonably assume that the data reflects only a smattering of information that police departments prefer hoard until local government pries it from them. The map shows surprisingly few data points in Manhattan and Brooklyn, for example, which may change in the coming year as New York City implements a new measure that finally obliges the NYPD to share basic information about surveillance technology. And most states have few or no laws governing the use and oversight of facial recognition (though numerous cities have banned it), to the extent that Microsoft, IBM, and Amazon have said that they’ll stop selling face recognition tech to law enforcement until it’s better regulated (or until a year is up, whichever comes first).

Interestingly, the map reveals that different areas prefer different flavors of surveillance. Ring cameras seem to be uber-popular in the suburbs of Chicago and Dallas; license plate readers are big in urban areas; rural areas seem to favor drones.

There may be gaps to fill; some things are just impractical or impossible to hunt down. For example, the data shows only a handful of contracts with Clearview AI, the gold medalist for invasive face recognition tech, mostly pieced together from news reports, although the New York Times has reported that more than 600 law enforcement agencies started using it in 2019. EFF senior investigative researcher David Maass told Gizmodo that many agencies no longer use Clearview AI’s highly controversial database or used it on a short-lived trial basis, and the project focused only on agencies that had publicly acknowledged that they had used the technology or had run a substantial number of searches through the system over the past year.

If you’d like to see another dot on the map, you can volunteer to help.

Updated: 7/15/2020, 5:34 p.m. ET: This post has been updated with additional comment from EFF senior investigative researcher David Maass, and to remove a reference to cell-site simulators along the Texas border.