Let us give thanks to Seattle’s City Council, which voted unanimously yesterday to force Uber and Lyft to pay their drivers the equivalent of local minimum wage and lifted the spirits of a sleep-deprived doomscrolling nation. The law, which will go into effect in January, ensures that drivers for ride-hailing companies get $16.39 an hour after expenses like fuel, insurance, and car maintenance. Oh, and all tips go directly to drivers too.

A July study by the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment at Berkeley found, with data from workers, that Seattle drivers have been averaging $9.73 per hour after expenses. Amazingly, a dueling Cornell University study, with data from Uber and Lyft, came up with over twice that estimate—$23.30 per hour. Berkeley researchers pointed out that the Uber/Lyft-sourced study did not factor in time between rides and seriously underestimates expenses. Nonetheless, Uber and Lyft hoped that Seattle would form its decision around study number two.

New York City was the first to pass minimum wage requirements for so-called “transportation network companies” in 2018, when the city’s Taxi and Limousine Commission voted to set payment at a minimum of $17.22 after expenses. The law was delayed by Lyft (which filed a lawsuit against the changes, and subsequently lost), but both companies were eventually forced to comply. Even Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi admitted that the terrifying wage requirement turned out fine for Uber. (As he told to shareholders: “overall, if you look at the dollar growth rate in New York, it’s still a healthy city for us.”)

In a statement shared with Gizmodo, Lyft vehemently rejected the idea that standardized wages help drivers. “The city’s plan is deeply flawed and will actually destroy jobs for thousands of people—as many as 4,000 drivers on Lyft alone—and drive ride-share companies out of Seattle.” (Confusingly, in the same email, Lyft also says it’s all for a guaranteed earnings floor. (Stipulations apply.) Lyft claims that the New York wage guarantee led to a loss of 10,000 drivers, who had to split limited shifts on more regimented schedules, saying that the figure was based on internal data.

Seattle’s City Council was unavailable for comment, but we’ll update the post if we hear back.

Uber declined to offer a statement but shared a September 14th letter to Seattle’s City Council. In it, they pointed to a large, honking drivers’ protest in New York City last year, after Uber announced that it would have to limit drivers on its platform. But the implication that Uber drivers are against wage standards is misleading. The Independent Drivers Guild, which organized the protest, has expressed a strong desire to see more regulation, including collective bargaining rights so that Uber and Lyft drivers can do things like set wage and benefits for times when they can’t work. Making the entire thing even more suspect, there have also long been doubts as to whether or not the IDG is a “company union,” due to its proximity to Uber leadership.

In August, Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi floated an astonishingly warped “third way” in the New York Times, in which gig companies set aside a cash reserve for “benefits [drivers] want,” based on the number of hours they work. Khosrowshahi actually said (in the New York Times, during a pandemic) that a driver averaging 35 hours per week would be able to use these funds to choose between either paid leave or health insurance premiums. That’s Uber’s manipulative “freedom” pitch, and Khosrowshahi didn’t specify that Uber has elsewhere defined relevant work hours as only time spent on trips.

Seattle’s law does not classify rideshare drivers as employees, something Uber and Lyft have opposed even more vehemently than wage floors. Specifically, in California, where lawmakers, the state Attorney General, and a judge have been waging a bitter battle to enforce that designation. Both Lyft and Uber have considered a pivot to a licensing model where they lend the brand to fleet owners, and managed to delay any drastic changes by threatening the nuclear option of leaving the state altogether.

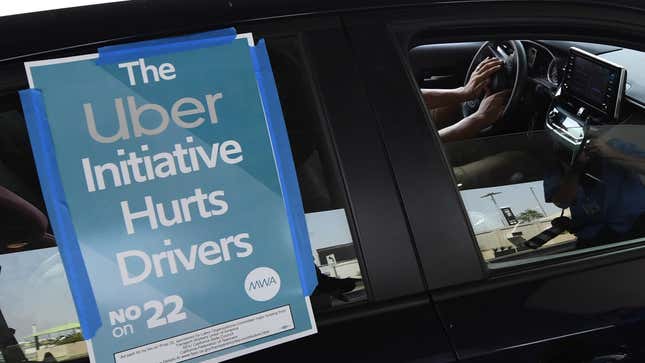

Uber and Lyft have put together their own ballot proposal, Prop 22,

for inclusion on the November 3rd ballot in California which, labor rights researchers argue, trades a baseline pay guarantee for total exemption from labor laws. Unsurprisingly they—along with a host of other gig work companies pushing Prop 22—have dumped loads of money into campaigning to pass this legislation, and have only gotten more aggressive in trying to court their own captive audience of drivers as November approaches.