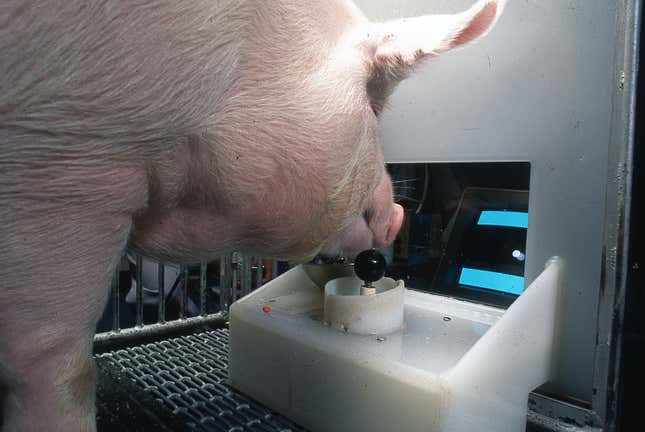

The four pigs came to win. If they played the game well, they got delicious dog food (they used to get M&Ms, but the humans decided those were too sugary). Time and again, when prompted by researchers to complete a video game task—guiding a cursor with a joystick, a sort of rudimentary Pong—they did so with impressive skill.

Researchers began putting pigs on computerized tasks in the late 1990s, and though the results got occasional press coverage over the years, no peer-reviewed research on the experiments has been published until today, with a paper in the journal Frontiers in Psychology. The scientists found that despite dextrous and visual constraints on the animals, pigs were able to both understand and achieve goals in simple computer games.

“What they were able to do is perform well above chance at hitting these targets,” said Candace Croney, director of Purdue University’s Center for Animal Welfare Science and lead author of the paper, in a phone call. “And well enough above chance that it’s very clear they had some conceptual understanding of what they were being asked to do.”

The published research is the long-awaited fruit of some 20 years of labor that began when Croney was at Purdue University, working with the prolific pig researcher Stanley Curtis. The project followed the efforts of two Yorkshire pigs, Hamlet and Omelet, and two Panepinto micro pigs, Ebony and Ivory, as they attempted to move a cursor to a lit area on the computer screen.

“They beg to play video games,” Curtis told the AP in 1997. “They beg to be the first ones out of their pens, then they trot up the ramp to play.”

“We’ve known for ages that pigs could do all sorts of learning and problem-solving. Any farmer can tell you this, and many scientists have demonstrated it,” Croney said. “What’s different here...is that the pigs had to grasp the very difficult concept that the thing they were manipulating (the joystick) was having its effect on a 2-dimensional computer-generated image (the cursor) that they could not touch, smell or interact with directly. That sort of conceptual learning is a huge mental leap for any animal, as this would never happen in the real world.”

“There is nothing in the natural behavior or evolutionary history of the pig that would have suggested they could do this to any degree,” Croney added.

It was an uphill battle for the swine. The joysticks were outfitted for trials with primates, so the hoofed pigs had to use their snouts and mouths to get the job done. All four pigs were found to be farsighted, so the screens had to be placed at an optimal distance for the pigs to see the targets. There were additional limitations on the Yorkshire pigs. Bred to grow fast, the heavier pigs couldn’t stay on their feet for too long.

“While there may have been some physical limitations to how well the pigs could see the screen or manipulate the joystick, they clearly understood the connection between their own behavior, the joystick, and what was happening on the screen,” Lori Marino, a neuroscientist unaffiliated with the current paper, said in an email. Marino, who directs the Whale Sanctuary Project, has long studied mammalian cognition, intelligence, and self-awareness, including in pigs. “It really is a testament to their cognitive flexibility and ingenuity that they were able to find ways to manipulate the joystick despite the fact that the test setup was often difficult for them to engage with physically.”

“What makes these findings even more important is that the pigs in this study displayed self-agency,” Marino added, “which is the ability to recognize that one’s’ own actions make a difference.”

The pigs were taught a number of commands to make their lives, as well as those of the researchers, easier. They learned directions similar to what you’d teach a dog—to sit, to come, to wait away from their pens when they needed cleaning—as well as to fetch their toys when the work of playing video games was over.

“At a certain point, they were getting really good at getting their toys and not so good at cleaning up after themselves,” Croney said. “I was becoming pretty much a pig daycare worker, going around and sorting them out. So then we started teaching them to put things back.”

When the research had concluded, the Yorkshire pigs were adopted by the owners of a bed and breakfast, where they lived out their lives on the farm. Ebony and Ivory eventually retired to a children’s zoo. Croney said that even years after the experiments, she went to visit Hamlet, who heard her voice and “came galloping” across the pasture to say hello.

Swine may not have the dextrous fingers of a primate or the doleful look of a puppy dog, but, cognitively, they are firmly in competition. Winston Churchill once said that “Dogs look up to you, cats look down on you. Give me a pig! He looks you in the eye and treats you as an equal.” It’s well past time we give pigs the respect they’re due.

This article has been updated with additional comments from Candace Croney.