It was a balmy day in Taiwan in November 2019, and I was rummaging through the Family Mart adjoined to the Qishan Bus Station. It was my last chance for 9V batteries and spicy tuna rice balls before taking a taxi into the mountains, where many of the remaining Indigenous languages of the island are spoken, the rest having been replaced by Chinese—the language of settlers from the Asian mainland who slowly took over the arable plainsland over the last few hundred years, as well as of the current ROC regime.

The 16 Indigenous languages still spoken in Taiwan today—the Formosan group—are tragically endangered, with three Formosan languages down to a single-digit number of speakers and a fourth rapidly encroaching. The languages are very well documented in some areas of their grammar and very poorly in others. The available documentation is the result of efforts by community members who create resources for their language’s revitalization movement and from local and foreign scholars.

The goal of my PhD dissertation project is to investigate one of the most poorly documented aspects of language. And I’m going to use a secret weapon, which I bought at B&H. To record, I use a Sony PCM-M10 recorder and a Røde Videomic, which I bought in a $379 bundle marketed to aspiring YouTubers, which I am not. Thankfully, it’s a directional (or ‘shotgun’) microphone, which records whatever you point it at louder than sound coming from other directions. This has allowed me to record analyzable elusive data in a sawmill, during a military drill, and while surrounded by dogs. (Not at the same time, luckily!)

The gaping hole in documentary linguistics which requires such equipment is something called prosody, which is easy to feel but hard to hear. To illustrate, I’m going to use a simple example from English.

How many sounds does English have?

You might be tempted to say English has 26 sounds, one for each letter of the alphabet. But that’s not quite right: Some letters like ‘c’ and ‘k’ can make the same sound. Some sounds, like ‘sh’ and ‘ng,’ aren’t represented by single letters in the alphabet. And how could we forget ‘ch’? Or, of course, ‘th’? How about the rising tone at the end of a question?

In school, we generally learn about two types of speech sounds: consonants and vowels. But I promise, there’s more! One layer of additional structure in our speech is stress. As Mike Myers demonstrates in View From the Top (2003)—“You put the wrong em-pha-sis on the wrong sy-lla-ble!”—in English, one specific syllable in multisyllabic words is more prominent than the others. Stress is one part of prosody, which is a large umbrella of speech phenomena that take place in larger domains like syllables and phrases, instead of smaller pieces like consonants and vowels.

But the real fun (if you’re me) begins when you ask how we know a syllable is stressed in the first place. The best clue is how the word interacts with intonation, the part of prosody that investigates how languages use tonal melodies.

For example, let’s say you’re at work, and someone walks into the break room and utters one of the following:

1. “There’s coffee.”

2. “There’s coffee?”

Same consonants and vowels. Same context. The first is a statement informing that there’s coffee. The second is a question, possibly where someone is surprised to hear that there’s coffee. Aside from periods and question marks, purely the domain of writing, what exactly is the difference between the two?

The most common approach to modeling intonation is by using the building blocks H (high tone) and L (low tone). A rise can be described as LH, and a fall as HL. These and longer melodies are used for one of two purposes: 1) a ‘pitch accent’ which marks a stressed syllable; or 2) a ‘boundary tone’ which marks the edge of a phrase (like a comma might do in writing).

These notations can get very nuanced. The gold standard model of English intonation, Janet Pierrehumbert’s dissertation, counts seven distinct pitch accent melodies: our good friend L+H*, as well as H*, L*, L*+H, H*+L, H+L*, and H+!H. The asterisk * here notes which tone in the melody is aligned with the stressed syllable. Pierrehumbert also counts four boundary tones: H- and L-, which mark minor phrase boundaries (like a comma), and H% and L%, which mark major phrase boundaries (like a period). While there have been efforts to tease apart how all of these are used, it’s not an easy task. Was that L*+H supposed to be sarcasm, or disbelief? Sass? Are they mad at me?!

Two of these elements have seen a fair amount of attention in pop science, specifically from non-expert authors who like to police millennial women’s speech. ‘Uptalk’ is just the recurring use of H-, and ‘vocal fry’ is what happens when one’s L% is low enough that the larynx produces creaky voice instead of modal voice. These two intonational elements have routinely been maligned as undesirable and even physically harmful: Naomi Wolf once called vocal fry a “destructive speech pattern.” In reality, elements like H- and L% are neither injurious nor uncommon in intonational systems. If the use of these elements is as bad for the English language as it’s made out to be, then I have bad news about a few thousand other languages.

How can we analyze intonation?

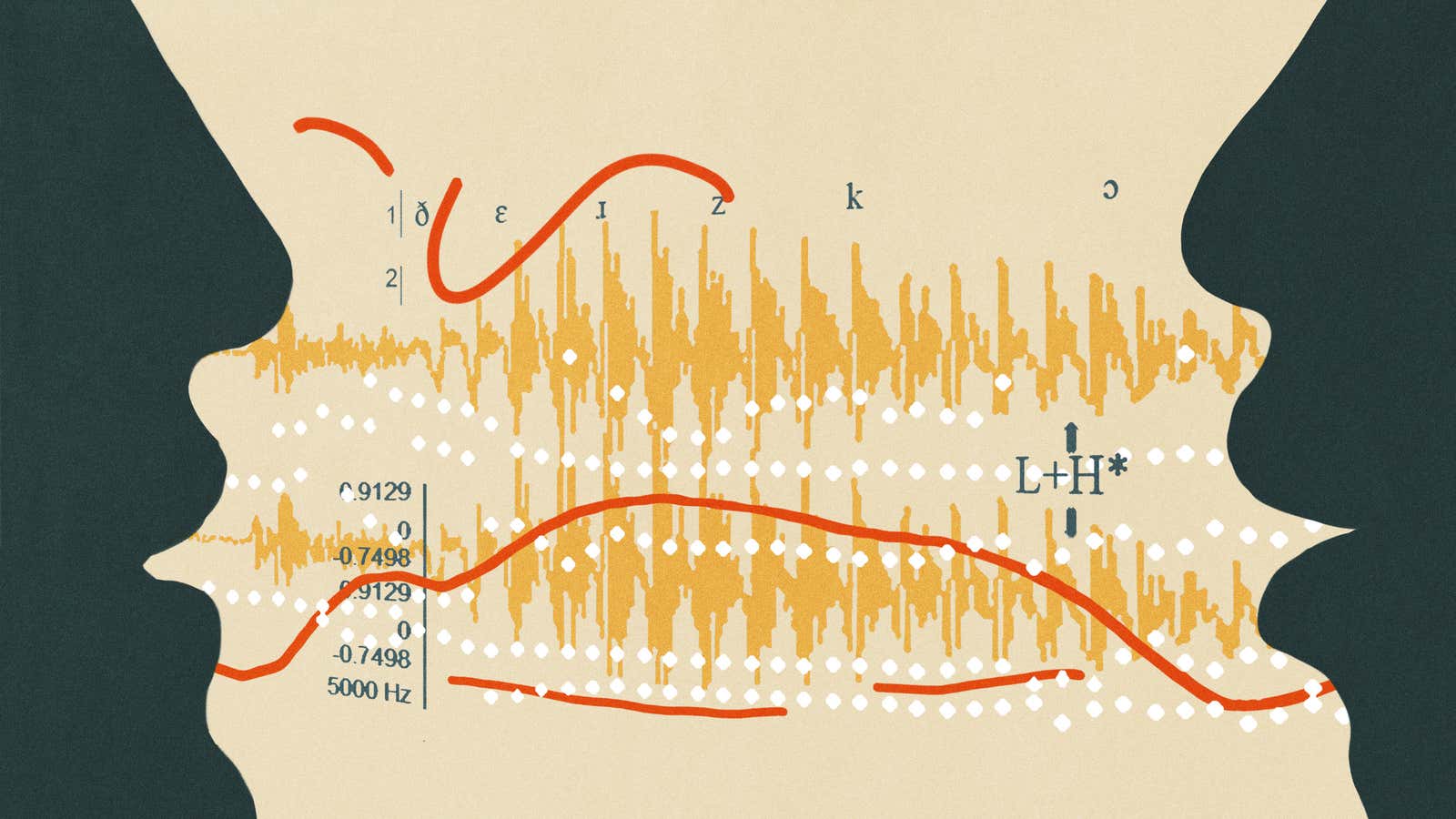

These days, analyzing a recording is easy enough. The most common software used in linguistics is called Praat, which is open source, thank goodness. Plunk in a .wav and you’ve got all of phonetics at your fingertips. If you can listen to your own voice on a recording without freaking out (I can’t), you should try it out yourself. Here’s a screenshot of “There’s coffee.” open in Praat:

Here, the waveform is shown on top, with the spectrogram in grayscale below. This shows all the frequencies sounding simultaneously at each point in time, with the different shades of gray showing the intensity of each frequency. Overlaid are the overall intensity (or ‘loudness’) shown with the yellow curve, the pitch in blue, and the formants (which are what make vowels sound different) in red.

On the bottom are two tiers of transcription, one with the consonants and vowels in IPA, a language-neutral way of transcribing speech sounds: [ðɛɹzkɔfi]. (I’ve written the ‘open o’ [ɔ] here, but I actually use [ɑ] instead because I’m not a true New Yorker. Shh!) The bottom transcription shows a label for L+H*, the pitch accent aligned with the stressed first syllable of coffee. It sounds like a rise in pitch, which reaches its crest towards the end of the syllable.

There’s plenty to look at here, but what we’re interested in is the pitch track. Praat actually has a more complex pitch-tracking system than what’s shown in the blue squiggles above, and you can manually filter out other detected frequencies. This is useful when you’re an incredibly awkward individual like myself, who often accidentally talks over their interviewees. If the pitch tracker picks up your embarrassing interruptions, you can just click them away on a screen like the one shown below. Here, the pink dots are frequencies included in the final pitch track, while the rest have been filtered out.

With your final, non-awkward pitch track, you can use Praat’s ‘smoothing’ tool with the default 10Hz buffer to smooth out the bumpiness. You don’t want a bumpy pitch track, like how embarrassing would that be? Once the pitch track is publication-ready, you can generate an illustration in the Praat Picture window, as you can see below.

“There’s coffee.”

It’s smoothed. It’s annotated. Our pitch track is *chef’s kiss* and now we have a much better view of what’s going on in our intonation. The rising tone of the L+H* pitch track is aligned with the stressed first syllable [kɔ] of coffee, and the utterance ends on a low tone shown by the boundary tones L-L% (as every major phrase boundary is also a minor phrase boundary).

Now compare this with the ‘question’ intonation.

“There’s coffee?”

Instead of a rise on the first syllable of coffee, there’s a low tone, so the pitch accent is L* rather than L+H*. And at the end of the utterance there’s a sharp rise, so the boundary tones are H-H% rather than L-L%.

Why don’t we see more intonation in descriptive linguistics?

Many of the world’s 7,000-ish languages are both endangered and poorly documented by linguists. And of the languages that do see dedicated study, prosody and intonation are often an afterthought. In ‘grammars,’ a type of book that serves as an in-depth description of all aspects of a language’s phonology and syntax, often based on years of field study, it’s not uncommon for the only mentions of prosody to be 1) which syllable in the word is stressed, and 2) an impressionistic description of the intonation on questions. (Spoiler alert: there’s probably a final rise.) That is not enough.

In the past, it made sense to omit prosody and intonation from field studies, as the recording and analysis equipment was bulky and expensive. I know I’m not lugging my phonograph and wax cylinders to the field! Worse yet, fieldwork often happens in noisy environments, and background noise can interfere with the analysis.

Røde’s directional mic, coupled with the pitch tracking in Praat, has allowed me to meet and work with speakers where they really speak, instead of needing to bring them to a lab. While any language can be used to describe anything, languages don’t exist in a vacuum, and the communities and cultures associated with a language are important context for linguistic study. This is especially so when eliciting intonation: Often, the best way to get a recording of a specific intonational contour is to be in a situation where it would naturally be used. If you want to get an English speaker to say “no, there are two dogs,” it’s going to be harder to conduct your interview in an empty recording booth than out in a dog park, for instance.

Unfortunately, the exclusion of prosody and intonation from descriptive linguistics has persisted into the current era, despite the increasing availability and utility of equipment. While there is growing interest in prosody/intonation, it is often in the form of standalone works. This has the drawback of being less-integrated with work on other aspects of phonology and syntax, even when they naturally interface with many aspects of prosody. We can only hope to see more H’s and L’s in grammars and other documentation work going forward.

What is intonation like in Taiwan?

The trip to Family Mart was part of my dissertation work, which sought to describe intonation in Formosan languages in terms of pitch accents and boundary tones, like Pierrehumbert’s model of English. I worked on as many languages as I was able to find speakers of, across four trips to the field in 2017-19, and wound up with original data on 10 languages/dialects. I managed about 20% of what I wanted to do, and wrote 800 pages about it.

Elicitation sessions involved everything from asking a native speaker to translate a word list to having them act out a dialogue or a real-world scenario that might evoke unique intonation. My favorite question to ask is “do you know any really long words?” which, as dumb as it sounds, will always either elicit a unique piece of data or at the very least break the ice. The longest words I found were a tie between kinamakasusususuan, the word for “family” in Piuma Paiwan, and maisasavusavuanʉ, the Saaroa word for “doctor”; both nine syllables.

The study resulted in a wealth of descriptive information about intonation in these languages. Some Formosan languages like Seediq and Saaroa had a pitch accent L+H* just like English, while others like Kanakanavu had a more complex pitch accent L+H*L, or just H*L as in Mantauran Rukai. Two languages, Amis and Kavalan, had glottal stops (like when British people say ‘butter’) that would show up at the end of statements but not questions. Some languages had unique intonation to show sarcasm or incredulity or to mark items in a list. And more importantly, what I found was merely the tip of a massive prosody iceberg, one that unfortunately is melting by the day.

How is covid-19 affecting language endangerment?

Endangered languages are such because the language is not being transmitted to younger generations, in favor of a dominant language like English or Chinese. This means that in many communities with an endangered language, it is the elders who speak the language. Given that age is a predictor for the severity of covid-19 infections, these speakers are especially at risk. Worse yet, many communities with an endangered language have used in-person classes as a major component of their language revitalization movement. These are difficult to conduct without putting these elder speakers, who often serve as the instructor, at increased risk of infection.

Taiwan’s prudent covid-19 response may have spared speakers of Formosan languages from some of what other communities facing language endangerment are going through with regard to the pandemic, however, language endangerment has been an issue in Taiwan well before covid-19. Of course, the difficulty and risk of international travel caused by the pandemic has also prevented linguists from working on languages outside their own country. Remote fieldwork could be an option given the increase in recording quality seen in newer smartphones, but this won’t work without pre-existing contacts, or if the technology isn’t available.

When languages lose their last native speaker, any information about the language that did not make it into the available descriptions is lost to history. Of course, it’s not just linguists around the world who are interested in language data: Many communities choose to revive their ancestral language after losing the last native speakers, based on archival materials. There has even been a shift, following certain Indigenous communities in North America, to thinking of languages as ‘dormant’ rather than ‘dead’ when they lose their last speaker, both to highlight their persisting cultural importance and to leave open the possibility that the language is reawakened by the community. When these communities do reawaken their language, many will not know how previous native speakers would distinguish statements from questions, or earnestness from disbelief, given the dearth of intonation in descriptive works.

Can technology help?

While writing this piece, I reached out to a colleague of mine, Joe Pentangelo, a fellow linguist and a postdoctoral fellow at the Macaulay Honors College, to ask how covid-19 has affected his fieldwork. Joe’s research concerns both endangered language documentation and the use of technology in the field. His PhD dissertation was the first use of 360º video for documentary linguistics, in which he used a Nikon Keymission 360 camera and Zoom H2N audio recorder to record interviews and organic conversations with speakers of Kanien’kéha (also known as Mohawk), as spoken in Akwesasne, a Kanien’kehá:ka community on the St. Lawrence river, which straddles the border between New York State, Ontario, and Quebec. The resulting videos can be viewed in any number of VR headsets and show the interviews and conversations in their original context, keeping intact all of the information about how speakers are interacting with each other that may be lost in laboratory work or audio-only recordings.

“The last recording trip I made up there was in December 2019, right before Christmas,” Pentangelo told me. “By the end of that trip, I had nearly 11 hours of immersive video, and the corpus was essentially complete. The plan was to return a few months later to screen all of the videos I’d recorded, to get final approval from all of the participants to release these videos publicly, and to work with local experts to transcribe and translate the content. Unfortunately, with the outbreak of covid, it hasn’t been safe to return, so the videos are not yet publicly released.”

One of the goals of Joe’s study was to make his corpus available publicly, allowing it to be a resource for the Kanin’kéhá:ka community rather than something primarily of interest to academics, a goal also reflected in the use of spontaneous conversations and recordings taken in situ. In Joe’s case, it is not only difficult to continue documenting the language, but even the bureaucracy involved in releasing the data publicly is at a standstill.

“I have been able to work remotely with Dorothy Lazore and Carole Ross, two educators from Akwesasne, to transcribe and translate content from some of the videos, but covid has greatly slowed the pace of this work, too,” he continued. “Still, I had enough of the project done to complete my dissertation… and I’m grateful that I’ll be able to continue this work—once it’s safe.”

There are some aspects of Joe’s project that have spared it many of the difficulties faced by other language documentation projects during the pandemic: the relationship between Joe and the Kanien’kéha speakers he worked with already involved a fair amount of technology, and he didn’t need to travel internationally to meet with speakers. Yet, the project has nearly ground to a halt just from the difficulty of basic things like moving around and meeting with people.

Despite the setbacks, more technology might be a way to mitigate the effects covid-19 has had on our ability to continue our efforts in language documentation. It may be a while yet before we can get on a plane and go interview people in an enclosed space with the confidence we had in 2019, but the steady march of language endangerment has not slowed, and documentation remains as important as ever. Hopefully some combination of tech like directional microphones and the normalization of virtual meetings will allow us to address how little we know about areas like prosody in the world’s languages, despite all of the logistical setbacks the pandemic has brought.

Ben Macaulay is a recent PhD in linguistics from The Graduate Center, CUNY, now based in Malmö, Sweden. His research focuses on prosody, intonation, and endangered language documentation.

Soundcloud images: Getty.