Illustration: Elena Scotti (Photos: Getty Images)

Ellen DeGeneres was supposed to host the 53rd Primetime Emmy Awards on September 16, 2001. But in the wake of September 11, the awards show was canceled twice, until finally, on November 4, DeGeneres hosted a more casual ceremony, to a seemingly reluctant crowd. It was an undoubtedly difficult task, to usher in something as frivolous as the Emmys while George W. Bush beat the drums of war. She quipped about the Taliban and told the audience, “They can’t take away our creativity, our striving for excellence, our joy.” The New York Times remarked the night was “marked” by “a tone of patriotism.” A critic at the Post-Gazette said, “the mix of patriotism and entertainment industry self-indulgence blended together surprisingly well.” For her efforts, DeGeneres received a standing ovation at the show’s end.

Her good-humored hosting was in stark contrast to the coverage of the 1998 cancellation of her popular eponymous sitcom Ellen. Though Disney and ABC executives cited poor ratings, it’s hardly a coincidence that the show’s demise came on the heels of her coming out. In 1997, she appeared on the cover of Time with the culture-shifting headline “Yep, I’m Gay,” and announced, “I never wanted to be the spokesperson for the gay community. I did it for my own truth.” Shortly after, her sitcom character (conveniently named Ellen) also came out in Season Four’s “The Puppy Episode.” In it, she falls for a gay woman, Susan (Laura Dern); after a series of gaffes, including coming out to her therapist and friends, she tells Susan the truth over an airport loudspeaker. After that, Ellen’s inevitable demise was one of Hollywood’s most notorious open secrets.

But, years later, standing in front of television’s biggest stars, DeGeneres smiled through the night. She embraced the whole Emmys audience in classic Ellen fashion, treating them as intimate friends and close family. Her bright disposition and patriotic melancholy obscured the stark reality: She was doing this song and dance for the same executives who had shut her out of Hollywood. They sat just out of the view of broadcast cameras, watching as DeGeneres performed what would become her signature niceness.

Ellen has since moved on from sitcoms, making her living with her popular daytime talk show, The Ellen DeGeneres Show, where she honed the cult of niceness that’s become the foundation for her public persona. But in recent weeks, a hairline fracture in DeGeneres’s reputation is beginning to widen into an uncontrollable chasm, rending apart a career she’s so tightly rebuilt. It’s a predictable conclusion to her decades-long project on The Ellen DeGeneres Show: assimilating into a Hollywood landscape that once brazenly excluded her. The “nicest woman in Hollywood” now faces numerous accusations of a set plagued by racism, harassment, and discriminatory labor practices. In hindsight, there could be no better explainer of her alleged behavior offscreen than her quest to rehabilitate her public image as the most non-threatening gay person on American television.

Ellen DeGeneres has come a long way from the girl born in Metairie, Louisiana, who worked as a waitress and part-time vacuum saleswoman before her standup career took off, and wrote jokes in what she’s since called a “flea-infested basement” in Texas. Nor is she a nervous 27-year-old performing her first stand-up gig on the Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson in 1986. She is a bonafide kingmaker, with influence and an audience reach that far outpaces contemporaries like Wendy Williams or the women who rotate through The View. The Ellen DeGeneres Show, which premiered in 2003, is irresistible to the most famous and powerful people in the world. Taylor Swift, Kim Kardashian, Mariah Carey, and Hillary Clinton have all appeared as guests. DeGeneres has also made hosting random civilians of the internet a kind of relatable trademark, posting their home videos of a tantrum or a funny-looking cat, giving them their 15 minutes of fame after an invite to DeGeneres’s soundstage. They are people like the viral “Star is Born” subway singer, or dancing children like Sophia Grace, or “Alex From Target,” the supposed hot Target cashier. (All have later been accused of being viral marketing hoaxes.)

By 1987, Ellen appeared on late-night television again, while she was traveling across the country doing stand-up before her work eventually expanded to scripted television. She was cast as a recurring character in 1989 on the short-lived sitcom Open House, playing a wacky secretary at a real estate agency. She made a string of appearances on other forgettable shows and nothing really stuck. Despite the string of bad luck, in 1994, she landed her first starring role on the ABC sitcom These Friends of Mine. In a gushy profile, New York Times reporter Bill Carter described DeGeneres’s look:

[Her] face stripped clean of makeup, dressed for comfort in jeans, a white T-shirt, and blue pin-striped blazer. Her only pass at what she would call “styling” is a newsboy cap squeezed down backward on her head, capturing all but an inch or so of her mid-length blond hair.

These Friends of Mine later became Ellen after Friends debuted in the fall. In an interview with the Times from 1994, she claimed she was “laughing out loud when I read the script.” Her vision for the show was clear.

“I knew what I could do with it. I wanted to do a smarter, hipper version of I Love Lucy, only don’t take it so far that I’m in a man’s suit with a mustache trying to fool Ricky that I’m not his wife. I wanted a show that everybody talks about the next day.”

Though DeGeneres envisioned Ellen as modernized classic television, critics claimed it was a slipshod adaptation of her signature humor. In a profile from 1994, DeGeneres said that the most common complaint she received about the first season was that it did not feel reflective of her typical humor. DeGeneres said she was often asked: “How come the show is not what you do?” The gargantuan effort on ABC’s part to rectify critics’ distaste of These Friends of Mine was largely because they seemed to believe in her viability. As the Los Angeles Times noted:

Moreover, DeGeneres, whose first act as a stand-up comic 14 years back consisted mainly of munching on a Whopper, has now become, more or less, the symbol of a network: ABC has announced that she will be the network’s spokeswoman in radio ads and on-air promos, personally introducing the debut of every show in ABC’s lineup this fall—an almost unprecedented vote of confidence.

In 1995, her broader popularity translated into a $1 million book deal, resulting in her debut, My Point… and I Do Have One. A critic for Entertainment Weekly claimed the humor in it was “subtle, delivery-driven, independent-minded,” but that print made her usual talents “crimped and unfocused.” Still, the network television machine continued spinning along, and Ellen had successful second and third seasons.

As her career progressed, so too did rumors around her sexuality, and in 1996, she began to indulge in some public foreplay with the assumptions about her. In character, she joked on the Larry Sanders Show that might sleep with a man if he was “feminine enough.” With Rosie O’Donnell, she cracked that her character was “Lebanese.” By the fall of 1996, it was leaked that the titular character was finally coming out of the proverbial closet.

In a retrospective on the months leading up to the episode’s eventual release, producer Dava Savel told HuffPost that the speculation and public scrutiny “was just horrible.” Cowriter Tracy Newman said that piles of hate mail poured into ABC studios and director Gil Junger remembered receiving calls at his home informing him he was going to hell. In a March 1997 story, the LA Times wrote that ABC would be finally filming the “long-anticipated episode,” snidely remarking it would “[end] a six-month guessing game that has left many pondering whether such a turn represents a breakthrough or, at this point, much ado about nothing.” In the days leading up to taping, a bomb threat was called into studio. What the LA Times saw as “much ado about nothing” had awoken a very public spectacle of homophobia and conservative panic.

As part of the press package for the “The Puppy Episode,” DeGeneres came out on the Time cover, looking approachable in a casual kneeling pose. She was rightly lauded for her bravery but, looking at the cover with the benefit of hindsight, it’s a stunning indictment of the conversation around gayness in the ’90s. Even before news of the episode leaked, the surveillance of her gender and sexual presentation bordered on outright fixation. When ABC moved to promote “The Puppy Episode,” that fixation turned to moral panic from conservatives and dismissal from liberal Hollywood outlets like the LA Times.

Even Time, entrusted with handling her coming-out spectacular, couldn’t escape the speculation surrounding her preferred presentation: often jeans, t-shirts, and little to no makeup.

“I hate that term ‘in the closet,’” says Ellen DeGeneres, the aforementioned sitcom star whose all-pants wardrobe and sometimes awkward chemistry with male ingenues was provoking curiosity from fans and reporters long before her sexuality became a minor national obsession.

“The Puppy Episode” premiered on April 30, 1997, and the scene in which Ellen comes out over the airport intercom was made charming by DeGeneres’s now sharply-honed persona. But still, advertisers like Wendy’s and Chrysler denounced the show. Companies pulled their advertisements, claiming it was “too controversial.” Conservative pastor Jerry Falwell remarked, “We don’t want her dumping that into the hearts and minds of the kids of America.”

DeGeneres soon appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show, which had aired “Letters to Oprah” segments in which audience members denounced both gay people and Oprah herself, for her role in the episode as Ellen’s therapist. DeGeneres told Oprah, nervously, that she knew her coming out was “big, but didn’t know it would this big.” She also said she didn’t know the marketing for the episode would “drag on” as long as it did.

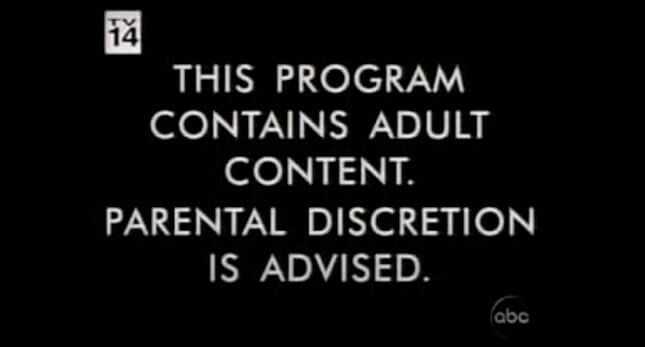

“The Puppy Episode” won Ellen awards, astronomical ratings, and commendations from progressive groups and LGBTQ+ rights organizations. But ABC and Disney’s promotion of the episode, which developed into more fleshed out “gay” plotlines on Ellen, seems in stark contrast to what came next. By the fifth season, ABC added parental advisory warnings to Ellen for its gay content. It also flashed a sentence before each episode, cautioning viewers: “due to adult content, parental discretion is advised.″ In October 1997, DeGeneres told TV Guide that ABC had forced her into a corner. “I never wanted to be an activist, but now they’re turning me into one.”

After its fifth season concluded, Ellen was canceled. The network cited poor ratings.

In an interview on Primetime Live in 1998, host Diana Sawyer grilled DeGeneres on whether or not her show was “too gay” for television. Sawyer asked if portraying gay characters on television was risking the comfort level of the viewer; DeGeneres retorted that even the bare-bones representation she was allowed was a “struggle” with ABC.

The reaction to the show, as Sawyer saw it, was that DeGeneres was “sneaking” gayness into the show, endangering her appeal with “mass audiences.” DeGeneres said that in the lead up to “The Puppy Episode,” she was combatting internalized homophobia, made worse by the publicity push. But still, DeGeneres stood by her decision, even though it cost her a primetime network show. “If I just had this one year of doing what I did on television, I’ll take that over 10 more years of being on a sitcom and just being funny,” she said.

ABC president Bob Iger saw it in a different way. He told Sawyer that ABC wanted DeGeneres to “slow it down” for viewers: “We’re not rooting for failure on-air,” Iger said. “The viewers primarily left because of sameness, not gayness. It became a program about a lead character that was gay every single week. And I just think that was too much for people.”

The years following Ellen’s cancellation were quiet for DeGeneres. She went public in 1998 with her relationship with Anne Heche, which lasted until 2000. She did a standup special that year and appeared in the television movie If These Walls Could Talk 2. While she maintained a cultural standing among fans and LGBTQ+ advocates and activist groups, her presence in the mainstream dwindled.

But that changed when she hosted the Emmys on November 4, 2001. Her role as the nice, soothing, patriotic host, meant to usher audiences through a more casual ceremony, was her reentry into Hollywood’s culture engine. Shortly after, on December 12, 2001, she hosted Saturday Night Live, either as a pairing with her Emmys press circuit or as a result of it.

The 2003 premiere of her talk show could be seen as a surprise. Two of DeGeneres’s sitcoms had already been canceled—why give her yet another platform?

The Emmys job is key to understanding DeGeneres’s successful return to television, especially in an increasingly conservative American landscape. Amid war and the troubling presidency of George W. Bush, viewers were hungry for light, fun-filled daytime fare, where celebrities sat smiling and the audience was always laughing. DeGeneres’s disarming persona, a unique disposition not found on other talk shows at the time, made for a casual environment that resisted any sense of external conflict. And as a celebrity herself, it wasn’t hard to lure famous guests to pad out the show’s first season. On September 8, 2003, DeGeneres launched the show with A-lister Jennifer Aniston.

Throughout the interview, Aniston seems nervous as DeGeneres shrugs and twiddles her thumbs and brings unprecedented casualness to the exchange. It feels almost intimate—as though it’s just two people in a living room having a conversation without any cameras or studio audience at all. The format became a staple of the show, but it also signaled a new direction for DeGeneres’s career. By the time Aniston, at the height of her Friends fame, sat on Degeneres’s brand new couch, the host had embraced Hollywood conventions—blandness, uniformity, assimilation—instead of railing against them. It was a new era of American conservatism, with viewers and advertisers skeptical of “others,” and so Ellen became America’s self-appointed niceness guru. As she told TV Guide, she never wanted to be an activist. She just wanted to be herself, on television.DeGeneres’s decision proved to be profitable: The Ellen DeGeneres Show was a critical and ratings success, winning 12 Daytime Emmys between 2004 and 2009, including Outstanding Talk Show Host for five years straight. Other awards included Producers Guild of America Awards, Peoples Choices Awards, GLAAD Media Awards, MTV Movie Awards, and Grammy and SAG Award nominations. Her 2007 Academy Awards hosting gig was also nominated for a Primetime Emmy. When she hosted again in 2014, she famously took a selfie with the night’s most celebrated stars. It quickly went viral, and there was perhaps no better indicator that DeGeneres, wedged between Meryl Streep and Bradley Cooper, had made it.

As DeGeneres was quickly becoming a fixture of daytime television, she began dancing after each monologue. This act was part and parcel of her appeal. Unlike the more serious fare of The Oprah Winfrey Show or the catty topicality of The View, DeGeneres veered toward internet-friendly, fluffy segments where she scared celebrities or asked them about their new dogs. She’d begin each show with thanking the audience for their applause, claiming she felt the same way about them that they so clearly felt about her. It was all very nice for her audience, primarily women between the ages of 25-54, a valuable demographic for advertisers.

Niceness is what DeGeneres has capitalized on, her Southern congeniality that saw her through the tumultuous pop culture landscape of aughts America, amid religious fundamentalism, multiple wars, and a crushing recession. Where her television presence was once a thing advertisers and executives fled from, her soundstage became one they flocked to. In 2004, she became a spokeswoman for American Express and, in 2008, for CoverGirl. She had come quite a way since being denounced by the same ad execs in the late ’90s.

Despite DeGeneres’s friendliness appealing to daytime audiences, the reality was less rosy. In the thick of the 2007 Hollywood Writer’s Strike, DeGeneres’s niceness started to show cracks when she crossed the picket line, stepping over 150 writers and staff who depended on her for a paycheck. The decision drew the ire of union members. In a follow-up report, Page Six revealed that an unidentified writer for her 2001 sitcom The Ellen Show claimed she treated writers “like shit.”

“We’d watch her in rehearsals, smiling and winning us over with her charm and comic timing. Then the director would yell cut, her face would fall, and she’d level a glare at the writers. ‘Why do you keep writing these unfunny jokes?’ she’d hiss. Ellen frequently eviscerated the head writer and […] boasted of the changes she’d make in season two, starting with his firing.”

That head writer, according to the unidentified staffer, went on to create Arrested Development and “win two Emmys for writing, and another for Best Comedy.”

And so, throughout the 2010s, DeGeneres danced and laughed and sung and smiled her way through a golden age, where the rose-colored glasses of viewers and studio executives alike saw her as a beacon of hope and progressivism. This image only began to falter in a 2018 New York Times profile, which announced that, “Ellen Degeneres is not as nice as you think.” As part of a press package for her then-latest stand-up special, she lamented her success, telling the Times she didn’t want to dance anymore. She was tired. But her show, as she saw it, was “escapism for what’s going on, one hour of feeling good.”

Her Netflix standup special, Relatable, centered her increasing detachment from modern life, as an excessively rich television executive. When the Times broached the subject of bubbling tabloid rumors that she was often a cruel boss, she shot the questioning down: “The first day [of Ellen] I said: ‘The one thing I want is everyone here to be happy and proud of where they work, and if not, don’t work here.’ No one is going to raise their voice or not be grateful. That’s the rule to this day.” Two years later, however, DeGeneres is facing allegations of a workplace plagued with racism and sexual harassment, from senior producers down. Employees also claimed she’d hired non-union workers to get out of paying them after production shut down and moved to remote filming. Then, on August 17, Variety reported that three senior producers had been fired from the Ellen show following a staff meeting between DeGeneres and her staffers, where she admitted she was “not perfect,” and promised to “come back strong” in the show’s 18th season. But despite the allegations—the admission via firings that Ellen was a deeply troubled institution—celebrity friends rushed to her defense. These included Kevin Hart, whose reputation she helped rehabilitate, or Katy Perry, who said that she’s “only ever had positive takeaways from my time with Ellen.”

But if celebrities came to Ellen’s defense, citing positive experiences and vague language about friendship, then Ellen herself had perfected the script. Shortly after she was criticized for sitting next to George and Laura Bush at a Cowboys game, DeGeneres turned to the very culture of surface niceness that she’s built. In response to loud criticism, she quipped during a monologue: “People were upset! They thought, ‘Why is a gay Hollywood liberal sitting next to a conservative Republican president?’ Didn’t even notice I’m holding the brand new iPhone 11.” She continued: “When I say, ‘Be kind to one another,’ I don’t mean only the people that think the same way that you do. I mean be kind to everyone.”

Her reaction revealed the contours of her longstanding project of assimilation. After a widely publicized and humiliating cancellation for reasons that were clearly rooted in homophobia, DeGeneres returned to television reborn, a host and spokeswoman as unassuming as her guests, or her clothes. When she does have queer guests on her show, they are usually white and cis, like the Rhodes Bros, gay teens who came out to their dad in a viral video in 2015. For their efforts, she gave them $10,000 as a sign of support.

Unlike Ellen, which was brasher in its foregrounding of gayness, DeGeneres returned to television declaring she would no longer rock the boat. She sits smiling across from A-list celebrities, asking about them about their favorite pedicure spots and snarking on her own public love life. Her politics are blandly liberal and her causes benign. To gain even an ounce of the power she now wields, DeGeneres had to change, to assimilate. She survived mass conservative gay panic only to, in an ironic twist, sell her soul to build a $300 million television empire. That’s clearly payment enough for Hollywood to see her through the next crisis.